Korean War Period - 25 June 1950 to 27 July 1953

At the end of WWII there was a massive downsizing (95%) of the US military. In retrospect it was excessive. What money was spent on new equipment was spent on weapons bound for Europe. There was no perceived threat from Asia until the North Koreans suddenly came south of the 38th parallel. When the U.S. Army left Korea, they took their tanks, heavy artillery and aircraft with them, leaving the South Koreans not much more than small arms. In the 5 years after WW II the U.S. military lost most of its senior officers with combat experience and the new officers were more “spit and polish” than combat oriented; see Incidents further on. Crash boats were part of the new, three year old U.S.A.F which was very much impressed with itself but knew almost nothing about its rescue boats and cared even less. With the activation of the Air Rescue Service, crash boats reverted to local airbase service organizations in March of 1950.The attitude was that "if it doesn’t fly, it doesn’t matter" and men who didn’t fly were “ball bearing WAFs”. The officer career path in marine operations had been terminated. At the end of WW II the Navy had burned PT boats rather than incur the cost of shipping them back to the U.S. Fortunately the USAF still had a few boats, but only a few, in the former Pacific Theater of Operations that were still serviceable.

At the start of the Korean War the USAF “brass” was still struggling with the army and navy to define its mission. The Air Force took the approach that “if it isn’t expressly prohibited, it must be permitted.” This opened the door for a group that eventually became the 22nd Crash Rescue Boat Squadron to engage in unconventional warfare in addition to it's traditional rescue role. In early July, 1950 the 6160th Air Base Group reactivated boat operations, forming Detachment 1, which in July of 1952 became the 22nd Crash Rescue Boat Squadron, officially based at Itazuke Air Base, Fukuoka, Japan with the primary maintenance facility at the Fukuoka shipyard. The Fifth Air Force Headquarters took charge of the unit, leaving only administrative duties to the 6160th. During the Korean War many of the traditional rescue operations were more and more executed by amphibious aircraft and helicopters, helping to free the 85 footers for special operations. Special or “spook” operations were a substantial portion, many crewmen say the majority, of their missions off North Korea. When the war started the last of the serviceable crash boats in the Far East were in storage in anticipation of eventually being shipped back to the U.S. Their crews had all been reassigned to other duties within the air force, most not marine related.

the army and navy to define its mission. The Air Force took the approach that “if it isn’t expressly prohibited, it must be permitted.” This opened the door for a group that eventually became the 22nd Crash Rescue Boat Squadron to engage in unconventional warfare in addition to it's traditional rescue role. In early July, 1950 the 6160th Air Base Group reactivated boat operations, forming Detachment 1, which in July of 1952 became the 22nd Crash Rescue Boat Squadron, officially based at Itazuke Air Base, Fukuoka, Japan with the primary maintenance facility at the Fukuoka shipyard. The Fifth Air Force Headquarters took charge of the unit, leaving only administrative duties to the 6160th. During the Korean War many of the traditional rescue operations were more and more executed by amphibious aircraft and helicopters, helping to free the 85 footers for special operations. Special or “spook” operations were a substantial portion, many crewmen say the majority, of their missions off North Korea. When the war started the last of the serviceable crash boats in the Far East were in storage in anticipation of eventually being shipped back to the U.S. Their crews had all been reassigned to other duties within the air force, most not marine related.

First Lieutenant Phil Dickey was given command of what was to become the 22nd CRBS, which included all crash boats in the Far East. In a position roughly equivalent to marine shop foreman was W.O. Don Slessler, a very dedicated, committed, and colorful individual. Lt Dickey’s first challenge was to re-assemble the crews and seaworthy boats. He found it easier to acquire seaworthy boats than crewmen. In re-assembling his crews Lt. Dickey found himself coming to the irritated attention of several senior officers, frantically trying to get their own units back up to full strength. Lt. Dickey arranged for a few supportive phone calls from headquarters that straightened out his superior officers, if not their anger toward the young officer. His word-of-mouth recruiting campaign throughout the crash boat alumni soon re-assembled his nucleus of eighty-five crewmen. Eventually there were over 400 men in the unit.

Upon activation of the squadron there was a fleet of 17 operational boats in theater total. Not all of those boats were available for service in Korea. Boats were based at the single air field in Guam, the single air field in Okinawa and at the 5 bases in Japan. Dickey had the following boats available to him: one 114 supply boat FS-47, the 104 ft. QS-15, six 63ft boats, R-2-711, 717, 1082, 1088, 1164, and 1196. He also was able to acquire four of the 85s, R-1-654, 664 ,667 and 676 which were sent to North Korean waters off the west coast of Korea. UN air forces lost one plane a day on average to hostile action over North Korea. The 63s were assigned to the Sea of Japan and the coastal waters of South Korea.

A seaman on the R-1-664, Bud Tretter, recalls slightly different numbers but appears to be referring to boats actually in Korean waters. The 22 CRB squadron consisted of (1) 24’ open cockpit “J” boat, (1) 42’ that looked like an old Chris Craft, (6) 63 footers, (1) 114’ “FP” boat and (4) 85 footers. Bud continues, “The FP boat was used to supply and refuel the boats stationed on the east and west coasts of the Korean peninsula, but below the 38th parallel, which only involved 63’s. No 63’s were operated north of the 38th. It is interesting to note that in the book "The USAF in Korea, Campaigns, Units, and Stations 1950-1953", compiled by the Organizational History Branch, Research Division, Air Force Historical Research Agency and published by the "Air Force History and Museum Program" in 2001 does not even mention the word "boat", much less the exploits of this small group of courageous men. In spite of the lack of recognition, the boats of the 22nd rescued over 308 aircrew members, made 793 medical evacuations, and transported more than 60 enemy POWs during the Korean War.

The four 85’s, (R-1-654, R-1-664, R-1-667, and R-1-676) operated out of an advance base near Inchon, on an island 50 miles north of the 38th. The island’s name was Cho-Do and was located approximately 5 miles off the Chinnampo River in area K-54. Cho-Do was a crescent shaped, rocky island with only primitive facilities. There was a small U.S. military facility one end with a helipad but no paved landing strip. Occasionally a C-47, the military version of the DC-3, would land on the beach. Gasoline for the boats was stored in 55 gallon drums grouped in small clusters along the beach so that an airstrike could not easily destroy all of them. They were towed in groups out to the boats for fueling. Later during the war a small fuel barge would bring out about 30 drums at a time and a pump to fuel the boats. Located in about the middle of the island was a very small fishing village. Rescue boats based in Cho-Do were under control of the 5th Air Force for special operations. There were no other U.S. boats or ships operated off the west coast above the 38th parallel.

Life on a crash boat off the coast of Korea was tough. Boats were stationed off the coast of Korea and over to Japan, moving constantly to stay under probable flight paths of aircraft going to and from several airbases. The boats had no functioning heating systems, so crews had to endure the frigid winter weather of Korea. Crews often lived aboard for two or three months at a time, returning to primaitve bases for fuel, water, and food. The need for major maintenance was the most common reason for returning to Fukuoka, Japan and "civilization". Although conditions were primative on the boats, most crew members readily admit that their living conditions were much better than the average infantryman during the war.

The tour of duty at Cho-do was one week. When a boat would return to Inchon from Cho-do, it would dock inside the tidal basin. The following day, fuel, water and food was delivered to the boat. Fuel was delivered to the boat in a tanker truck . Food would arrive in a 6x6 truck. "We would receive about 20 loaves of bread. several large 4"x4"x14" tins of spam, and many cans of vegetables." Bud continued, "we would receive a crate of potatoes and a crate of fruit either oranges or apples. In addition, we would get a box of 101 rations. This box would include cartons of cigarettes, boxes of Snickers and Milky Way candy bars, 6 bars of Cashmere Bouquet soap and a few other miscellaneous items. Most everything was tainted with the fragrance from the soap."

A nearby U.S. Army truck motor pool at Inchon had established a shower area. Black barrels of water were on a 15ft high cliff and water was gravity fed to the sprinkler heads below. Get wet, soap down and wash off quickly to conserve the water. The boat crews were given access to these shower facilities. This was a cold water shower that was operational in warm weather only. When they would return to Inchon, there was a laundry boy that would pick up the fatigues, sweat shirts etc. and wash them. When the sheets on the beds were brown, they were towed behind the boat to wash them.

The four 85 ft. boats operated in pairs. The R-1-654 and the R-1-667 would operate as a pair and the R-1-664 and the R-1-676 would operate as a pair. One pair would operate out of Inchon at a time. One of the boats in a pair would go to Cho-do for a week and then would be relieved by the other boat of the same pair on a weekly rotational schedule. On one occasion the R-1-676 hit a sand bar and pushed a strut through the bottom of the hull and had to return to Fukuoka, Japan for repair. The R-1-667 replaced the R-1-676. This accident required the R-1-664 to remain on duty at Cho-do and additional week. There were no food provisions for this second week. Bud continued, "Old Quaker Puffed Oats cereal from the 101 rations we had in storage were used as well as some liver obtained from the USAF radar men on Cho-do island by trading 25 lbs. of sugar. We obtained a case of condensed milk from a British ship that was in the area".

Milton Seagrave, another veteran of Korean crash boat life, clarified Bud's comments by writing that one pair, let's say P-654 & P-667, would be stationed in the basin at Inchon. One of that pair, P-654 would go to Cho-do island for a one week stay. At the end of the week, the other boat of the pair, P- 667 would go to Cho-do to relieve the P-654. The two boats would be together at anchor at Cho-do Island overnight. Early the next morning, the first boat, P-654 would depart Cho-do Island enroute to Inchon to take one fuel, food, showers for the crew and be prepared to return to Cho-do at a moment's notice.

The second pair, P-676 and P-664 would be in Fukouka, Japan for general maintenance or repairs in the Japanese shipyard. When a boat at Fukouka was in operating condition, it was available to perform emergency missions to southern Korea as needed or take a stand-by position around southern Korea to relieve a 63 ft. boat that needed to go to Fukuoka for R & R, general crew rotation, repairs, etc. Typically, one pair of boats would be doing the Inchon /Cho-do rotation for a few weeks while the other pair of boats were receiving maintenance or doing rescue work.

At times the pairings were difficult to maintain. Milton wrote that on one occasion the P-664 went to the shipyard to get a propeller shaft and strut installed, new engines and a quad .50 cal installed. After departing the shipyard, the P-664 was ordered on assignment at Kunsan air base, on the lower southeast coast of Korea. Subsequently she was ordered to relocate to Inchon, Korea to take on fuel and rations and proced to Cho-do to complete the rotation of the P-667 and relieve the P-654. The P-667 was returning to Fukouka, Japan, for needed repairs. The P-654 had completed their weekly stay at Cho-do when the P-664 arrived to relieve them. The P-654 returned to Inchon and then to Fukouka. The P676 was ordered to Inchon to take on fuel and rations and to proceed to Cho-do Island to relieve P-664 at the end of her weekly rotation. At last, the boat pair P-664 and P-676 were together again, performing weekly rotations to Cho-do Island. That was easy to follow, wasn't it?

Bud Tretter continued, R-1-664 carried a 14 man crew of Americans, 4 of which were engineers; 1 cook; 1 medic; 1 armorer; skipper; mate; and 4 deckhands, plus a couple of Koreans as interpreter / houseboys. They carried 500 gallons of fresh water, which was mainly used for drinking, and cooking. Showers were out of the question. During the winter they did get an occasional shower from either a U.S. navy destroyer or a British frigate.

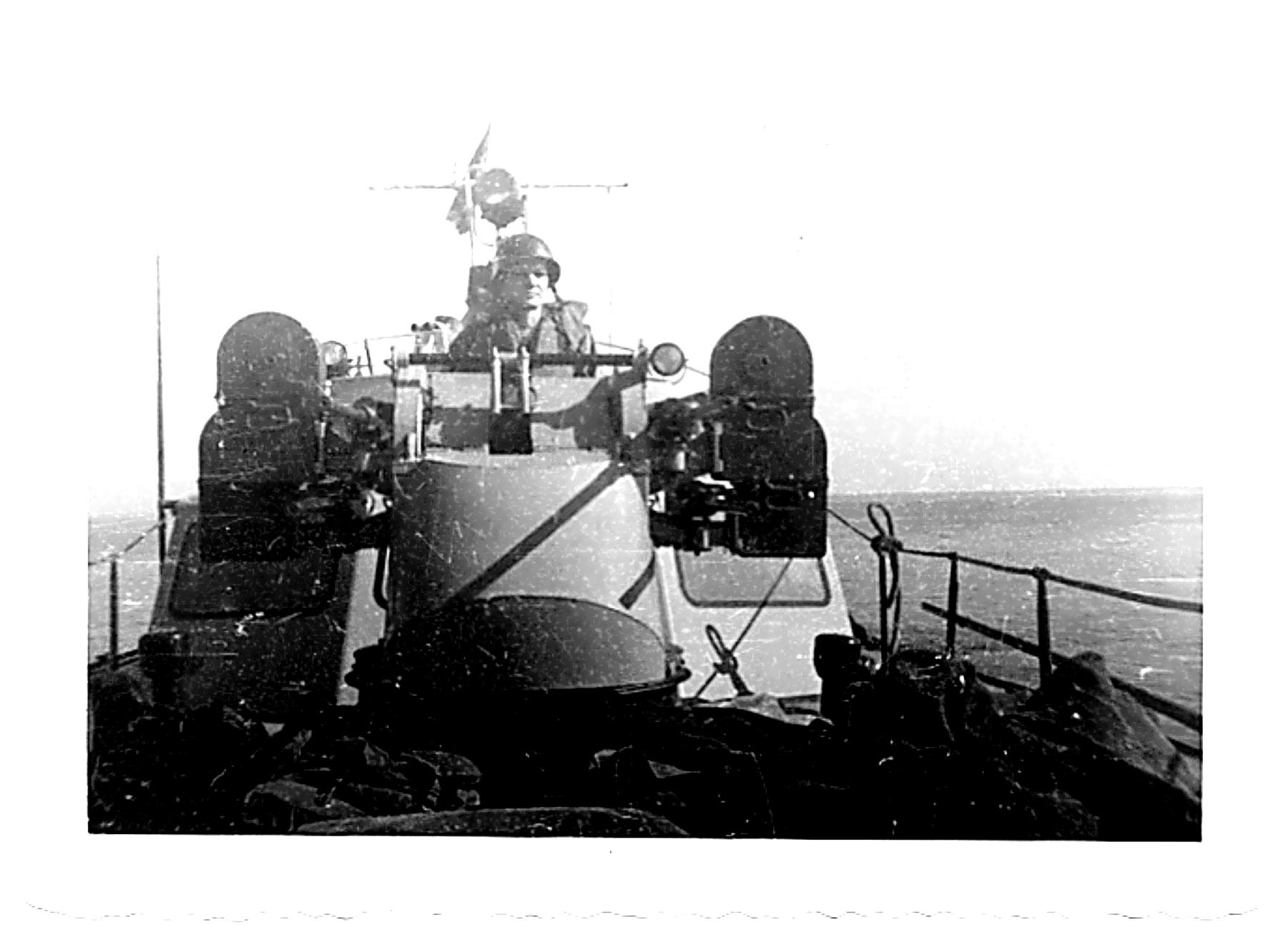

The 85s that served in Korea commonly had their armament modified. The 20mm anti-aircraft gun in the rear cockpit was replaced with a single .50 caliber gun. The 20mm had a shorter effective range which limited its use against jets and overkill for Bed Check Charlies. It would have also complicated their inventory and supply chain. The twin .50 caliber guns and their mounts in each tub, were removed at the end of World War II, regardless of whether the boat was being mothballed or to be sold in the civilian market. None of the crash boats were armed in peace time. At the start of the Korean War the original twin .50 mounts were no longer available, so the Army truck style single .50 gun rings were installed on the tubs, along with the faster firing USAF Browning M3 single .50 cals instead of the Army M2. A "quad fifty" was installed on the forward deck, first by running an approximately 3” steel pipe with a saddle on the bottom from under the deck straight down to the keel, and then a steel plate was mounted to the deck to withstand the pounding of the recoil, and finally the “quad-fifty”. That is four fifty caliber machine guns with a combined output of 2,000 rounds per minute. This arrangement was used to engage armed enemy junks and shore resistance during special operations more often than to defend against enemy aircraft.

Milton Seagraves, Gunner The back end of a Quad Fifty

Milton Seagraves, gunner on the R-1-664, gave me this description of the quad mount. The quad-fifty had a gasoline engine that powered the rotation and elevation of the guns. It is the same type of gun mount found on an Army half-track. It had inverted V hand grips on a stand for controlling the guns and the gun site mounted on a cross bar. The quad mounts were mounted on the boats when they were in Japan for repair or engine changes. The mount on the R-1-664 was installed in late October of 1952 and available for use from that time to April 1953. Milton was the gunner in the mount and two seamen were assigned as ammo carriers. Each "tombstone" canister weighed about 80 pounds with 200 rounds of ammunition.

Milton was deployed to Itazuki AFB in Fukuoka, Japan working as an aircraft armament man on the flight line removing, cleaning, installing and sighting in the .50 caliber machine guns on fighter planes. (F-80 F-82, F-84, F-86 and F-94) He also loaded 5 in. rockets on F-82 aircraft.

The Crash Boat Squadron was also at Fukuoka, Japan. One of the men on a Crash Boat removed and disassembled a .50 caliber machine gun and when he reassembled it he did not set the headspace correctly. When he attempted to fire the gun, the bolt lock did not engage and the gun exploded blowing brass cartridge particles out the bottom of the gun into his legs.

The Crash Boat Squadron requested an armament man be assigned to train the crews to properly assemble the guns. Milton was not in good standing with his sargent at the armament shack so he got transferred to the 22nd Crash Boat Squadron. He was also knowledgeable of gas engines so he was assigned to assist the Japanese mechanics overhaul the Packard V-12 engines and the smaller Chrysler Marine engines in the smaller J boats.

His initial assignment was on the R-1-667 at Inchon, Korea. The boat got damaged so he was reassigned to the R-1-676 with Skipper O'Haver as an armament man, gunner and assistant engineer. He was responsible for training the crew members on use and maintenance of the .50 caliber guns. Any time a gun was fired, he cleaned it and returned it to service.

They carried a variety of rifles and submachine guns. They had Carbines, Garands, .45 caliber Burp Guns, Thompson .45 caliber drum magazine machine gun and a 57mm recoilless rifle. The 57mm rifle was taken from the office of Warrant Officer Donald (Nick) Nichols at Kimpo Airfield, in Seoul, Korea. Don Nichols was the source of their special operations.

I have not had the opportunity to meet any WWII crash boat vets but there are some things that I have noticed. Many of the men who were initially put in positions of authority had some very minimal boating experience, especially in WW II, whether recreational or commercial. If you came in knowing that the “pointy end of the boat” was the bow, you were “experienced”. A large percentage of them continued with some sort of mechanical or electrical related career. In retrospect, many thought their best time in the service was their time on the boats. This was especially true for those who continued to serve after Korea to December, 1956 when the crash boat service was officially disbanded. For many, after Korea, service often included some very pleasant locations such as Bermuda, the Caribbean, and southern U.S. waters such as West Palm Beach (Morrison Field, now PBI) and Tampa. In West Palm Beach, the base was located on Peanut Island, at the inlet from the Atlantic to the Intracoastal Waterway. There was a 63 ft. crash boat, a 57 ft. yawl, and trips to the keys and the Bahamas, not to mention fishing trips and other recreational pursuits.

One bad thing about being on the boats all the time during Korea was that, according to Bob Hoffer, a person did not get to know very many guys, except as a name and what boat they were on. "Just wave and head out to sea. We were like ships in the night. Too bad it took forty years or so to enjoy their company and conversation for any length of time."